The River That Owns Itself

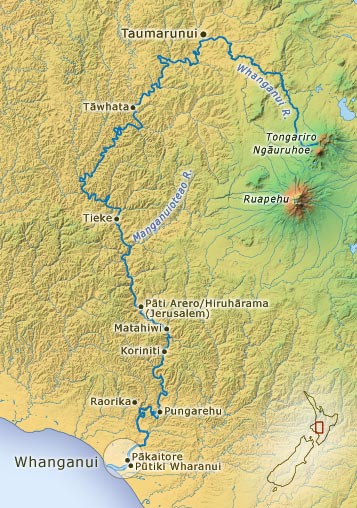

The Te Awa Tupua (Whanganui River Claims Settlement) Act 2016 has been passed by the Parliament of New Zealand and gives effect to the Whanganui River Deed of Settlement signed on 5 August 2014, which settles the historical claims of Nga Tangata Tiaki o Whanganui, the seven Whanganui Iwi who had Treaty of Waitangi claims relating to the Whanganui River. It declares the river to be:

The Te Awa Tupua (Whanganui River Claims Settlement) Act 2016 has been passed by the Parliament of New Zealand and gives effect to the Whanganui River Deed of Settlement signed on 5 August 2014, which settles the historical claims of Nga Tangata Tiaki o Whanganui, the seven Whanganui Iwi who had Treaty of Waitangi claims relating to the Whanganui River. It declares the river to be:

‘[A]n indivisible and living whole, comprising the Whanganui River from the mountains to the sea, incorporating all its physical and metaphysical elements.’ -s12

and that

‘Te Awa Tupua is a legal person and has all the rights, powers, duties, and liabilities of a legal person.’ -s14(1)

According to Attorney-General and Treaty Settlements Minister, Christopher Finlayson:

“The Crown will not own the river bed. The river will own itself. That’s a world-leading innovation for a river system.”

This marks the conclusion of the longest-running piece of litigation in New Zealand legal history and is particularly remarkable in extending legal personality to the Whanganui River. Although, this is not a first in New Zealand as Te Urewera (a former national park) was granted legal personality in 2014.

This marks the conclusion of the longest-running piece of litigation in New Zealand legal history and is particularly remarkable in extending legal personality to the Whanganui River. Although, this is not a first in New Zealand as Te Urewera (a former national park) was granted legal personality in 2014.

The most common confusion about this law is that the river is being made a natural person, the same as a human, with human rights. This was at the centre of much of the mainstream media commentary and some prominent commentators conflated the two concepts of the Natural Person and the Legal Person.

Natural Persons and Legal Persons

So what is the difference? A Natural Person is a human. A Legal Person is one of the many entities that can be created at law. Legal Persons include companies, trusts, incorporated societies, even ships. They are all entities that are capable of having legal rights, duties and obligations such as suing and being sued, and entering into contracts.

Only a Natural Person can have human rights to the fullest extent but Legal Persons can have a right to, for instance, freedom of expression or natural justice. Any right that it makes sense for a Legal Person to have will also be accorded to the river. If the river is by any legal means considered to be supplying goods and services, it will be liable to pay the Goods and Services Tax the same way that a company would. If corporate manslaughter laws were introduced in New Zealand it would be possible that the river could be held liable for the death of anyone who drowned although it stretches the bounds of our understanding of liability to understand how it would be enforced in the civil or criminal realm.

This all seems very abstract at first blush so it is helpful to look at the origins of this idea and the problems it was designed to solve. I wrote about this in my Master of Laws thesis at the University of Auckland in 2010 and have summarised my research below.

Should Trees Have Standing? The Problem This Solves

The concept of extending legal personality to non-human nature has an interesting and (certainly in legal terms) recent lineage. The idea entered the academy in a seminal law review article published forty five years ago, Christopher D. Stone’s, “Should Trees Have Standing? – Toward Legal Rights For Natural Objects” (Southern California Law Review 45 (1972) 450-501).

Stone conceived of the idea as a way to overcome the limitations imposed by viewing nature as property. He highlighted the absurdities of the granting of legal ‘personality’ to corporations and even to ships but not to animals, trees, rivers and ecosystems. The legal difficulty was (and in most of the world remains) that only parties who could demonstrate to the Courts that their property or civil rights had been unjustifiably prejudiced could bring an action under law – if not, they lacked the standing to bring an action under law. Courts have traditionally construed this bar to be a high one and so this problem of standing has been the major obstacle to legally defending non-human organisms and ecosystems as a whole unless a competing property right can be shown.

Stone conceived of the idea as a way to overcome the limitations imposed by viewing nature as property. He highlighted the absurdities of the granting of legal ‘personality’ to corporations and even to ships but not to animals, trees, rivers and ecosystems. The legal difficulty was (and in most of the world remains) that only parties who could demonstrate to the Courts that their property or civil rights had been unjustifiably prejudiced could bring an action under law – if not, they lacked the standing to bring an action under law. Courts have traditionally construed this bar to be a high one and so this problem of standing has been the major obstacle to legally defending non-human organisms and ecosystems as a whole unless a competing property right can be shown.

Stone’s innovation was to propose that the interests of the voiceless in nature should be represented by a guardian or trustee; Unlike a conventional fiduciary relationship in law, it is not necessary for a special relationship or set of circumstances to give rise to this obligation – any legal person may bring an action on behalf of the non-human. This then imposes liability on the party causing the harm upon the guardian’s showing that the integrity of the organism or ecological system has been compromised, notwithstanding the economic harm to any human. The judgment given is for the benefit of the ecosystem or organism, the party causing the harm must make such compensation as is necessary to ‘make whole’ the organism or system. They would pay compensation into a fund from which the guardian would draw.

Te Pou Tupua: The Human Face of the River

There are two people, Te Pou Tupua, who are to act as the ‘human face’ of the river, appointed jointly from nominations made by iwi (one of the Māori tribes) with interests in the Whanganui River and the Crown. Their role is to ‘act and speak on behalf of the Te Awa Tupua [the river] … and protect the health and wellbeing’ the river. The Pou Tupua will be ‘supported’ by Te Karewao, an advisory committee comprising representatives of Whanganui Iwi, other iwi with interests in the River and local authorities. The Pou Tupua will enter into relationships with relevant agencies, local government and the iwi and hapu (Māori sub-tribe) of the river.

This is a full and final settlement. The Crown-owned parts of the bed of the Whanganui River and its tributaries will vest in Te Awa Tupua through the settlement legislation. No private land is involved. Existing public access rights and the use of the river, including navigation rights, will be preserved and are not affected by the vesting of the bed of the river. The settlement does not affect water rights or create ownership of water; the vesting of the Crown-owned riverbed does not create or transfer any proprietary interests in water.

The settlement’s total cost to the Crown is $81 million: $30m for the establishment of Te Korotete (a fund to support the health and wellbeing of the river); $200,000 per year for 20 years for Te Pou Tupua (the “face” of the river, or the two natural persons appointed to act for the river); $430,000 for the establishment of Te Heke Ngahuru (a strategy established to ensure the future environmental, social, cultural and economic health and wellbeing of Te Awa Tupua).

‘Rights of Nature’ in the 2008 Constitution of Ecuador

The 2008 Constitution of Ecuador was the first national-level legal instrument ever to incorporate recognition of the intrinsic worth of non-human nature.

Articles 71, 72 and 397 of the 2008 constitution affirm the elimination of the ‘standing’ requirement. Articles, 73 and 74 are the most closely ‘related principles’ as mentioned in Article 71. These affirm the ecological integrity that predicates the assigning of value to nature beyond that of property:

Article 71: Nature or Pachamama, where life is reproduced and exists, has the right to exist, persist, maintain and regenerate its vital cycles, structure, functions and its processes in evolution. Every person, people, community or nationality, will be able to demand the recognitions of rights for nature before the public organisms [note: This refers to the public bodies that will adjudicate or review such claims]. The application and interpretation of these rights will follow the related principles established in the Constitution.

Article 72: Nature has the right to an integral restoration. This integral restoration is independent of the obligation on natural and juridical persons or the State to indemnify the people and the collectives that depend on the natural systems. In the cases of severe or permanent environmental impact, including the ones caused by the exploitation on non-renewable natural resources, the State will establish the most efficient mechanisms for the restoration, and will adopt the adequate measures to eliminate or mitigate the harmful environmental consequences.

Article 73: The State will apply precaution and restriction measures in all the activities that can lead to the extinction of species, the destruction of the ecosystems or the permanent alteration of the natural cycles. The introduction of organisms and organic and inorganic material that can alter in a definitive way the national genetic heritage is prohibited.

Article 74: The persons, people, communities and nationalities will have the right to benefit from the environment and form natural wealth that will allow wellbeing. The environmental services cannot be appropriated; its production, provision, use and exploitation, will be regulated by the State.

[…]

Article 397: In the case of environmental damage, the State will act immediately to ensure the health and restoration of the ecosystem. In addition to the appropriate sentence repeated the state against the operator of the activity that caused the damage on the obligations of reparation, under the conditions and procedures established by law. Responsibility also rests on the server or servers responsible for environmental monitoring. To secure the individual and collective right to live in a healthy and ecologically balanced environment, the State agrees to:

-

Permit any natural or legal person, group or collective human right to take legal action and seek judicial and administrative bodies, subject to its direct interest, for the effective protection of those on the environment, including the possibility of applying for injunctions to stop the environmental damage or threat of litigation matters. The burden of proof regarding the absence of actual or potential harm is upon the manager of the activity or the defendant.

Community Environmental Legal Defence Fund and Ecuador’s Constituent Assembly

The importation of the constitutional provision for Rights of Nature has followed an interesting trajectory. The 2008 Ecuadorian Constitution was drafted in a participatory process by a body called the Constituent Assembly that travelled around the country consulting widely with domestic civil society groups and indigenous communities as well as overseas NGOs. Among others, the Constituent Assembly worked with the Pennsylvania, US-based public interest law firm, the Community Environmental Legal Defence Fund (CELDF), in concert with the Pachamama Alliance, an NGO based in San Francisco, USA and Ecuador. A delegation from the CELDF visited Montecristi, Ecuador on two occasions in November 2007 and February 2008 to consult with the Constitutional Assembly as a whole and with several Mesas (committees).

Although the incorporation of legal recognition for non-human organisms was unprecedented in national constitutions, the CELDF had in fact drafted similar provisions for municipal bodies in the US.

On September 19, 2006 a pioneering Ordinance (see Section 7.6 of the link) was passed into law by the Tamaqua Borough Council in Schuylkill County, Pennsylvania. This locality was radicalized by years of suffering negative environmental and health consequences of private companies using human waste (‘sludge’) to fertilise fields in the district, then evading liability through the use of corporate structures. The 2006 Ordinance made the Tamaqua borough the first municipality in the United States to recognise Rights of Nature and also to permit residents to bring lawsuits to vindicate those rights. The Tamaqua law also (1) banned corporations from engaging in the land application of sludge within the Borough; (2) recognized that ecosystems in Tamaqua possess enforceable rights against corporations; and (3) asserted that corporations doing business in Tamaqua will henceforth be treated as “state actors” under the law, and thus, be required to respect the rights of people and natural communities within the Borough. Similar provisions have now been passed in over 100 municipalities in Pennsylvania and Maine.

The wording of Articles 71 and 72 in the Ecuadorian constitution recognizing the rights of nature are closely based on that used in the 2006 Tamaqua Ordinance. The precise wording recommended to the Ecuadorian Constitutional Assembly by the CELDF was as follows:

Natural communities and ecosystems possess the inalienable right to exist, flourish, and evolve within Ecuador. Those rights shall be self-executing, and it shall be the duty and right of all Ecuadorian governments, communities, and individuals to enforce those rights. Suits brought to enforce those rights shall be filed in the name of the natural communities or ecosystem whose rights have been violated, damages shall be awarded to fully restore the natural communities or ecosystems, and awarded damages shall be applied exclusively towards returning the natural community or ecosystem to its previous state.

The main difference to note is that the constitution as passed leaves greater discretion as to how the damages are to be applied. Rather than the paying of damages into a dedicated fund as was also the original formulation of Professor Stone, the state will establish ‘the most efficient mechanisms’. This is not necessarily a dilution of the original intention, it may well allow for more practical measures such as restoration or mitigation schemes. It may also close the door on the possibility of ‘efficient breach’ by companies who stand to profit nonetheless.

Below is a relevant excerpt of the Chen Palmer | New Zealand Legal Research Foundation Lecture I gave in 2013 at the University of Auckland Law School based on this work in my LL.M thesis. The clip that follows (5/5) covers the process of the CELDF working with the Ecuadorian Constituent Assembly to introduce the Rights of Nature law into the constitution.