The River That Owns Itself

The Te Awa Tupua (Whanganui River Claims Settlement) Act 2017 has been passed by the Parliament of New Zealand and gives effect to the Whanganui River Deed of Settlement signed on 5 August 2014, which settles the historical claims of Nga Tangata Tiaki o Whanganui, the seven Whanganui Iwi who had Treaty of Waitangi claims relating to the Whanganui River. It declares the river to be:

The Te Awa Tupua (Whanganui River Claims Settlement) Act 2017 has been passed by the Parliament of New Zealand and gives effect to the Whanganui River Deed of Settlement signed on 5 August 2014, which settles the historical claims of Nga Tangata Tiaki o Whanganui, the seven Whanganui Iwi who had Treaty of Waitangi claims relating to the Whanganui River. It declares the river to be:

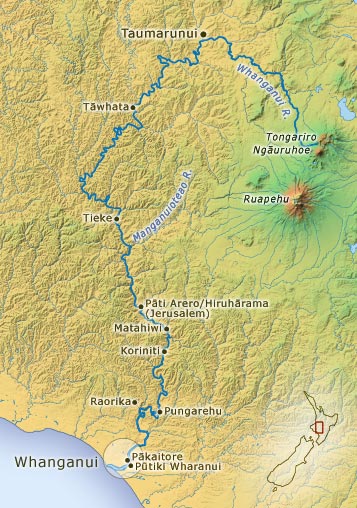

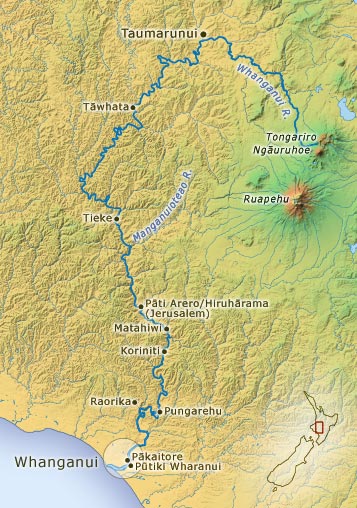

‘[A]n indivisible and living whole, comprising the Whanganui River from the mountains to the sea, incorporating all its physical and metaphysical elements.’ -s12

and that

‘Te Awa Tupua is a legal person and has all the rights, powers, duties, and liabilities of a legal person.’ -s 14(1)

According to Attorney-General and Treaty Settlements Minister, Christopher Finlayson:

“The Crown will not own the river bed. The river will own itself. That’s a world-leading innovation for a river system.”

This marks the conclusion of the longest-running piece of litigation in New Zealand legal history and is particularly remarkable in extending legal personality to the Whanganui River. Although, this is not a first in New Zealand as Te Urewera (a former national park) was granted legal personality in 2014.

This marks the conclusion of the longest-running piece of litigation in New Zealand legal history and is particularly remarkable in extending legal personality to the Whanganui River. Although, this is not a first in New Zealand as Te Urewera (a former national park) was granted legal personality in 2014.

The most common confusion about this law is that the river is being made a natural person, the same as a human, with human rights. This was at the centre of much of the mainstream media commentary and some prominent commentators conflated the two concepts of the Natural Person and the Legal Person.

Natural Persons and Legal Persons

So what is the difference? A Natural Person is a human. A Legal Person is one of the many entities that can be created at law. Legal Persons include companies, trusts, incorporated societies, even ships. They are all entities that are capable of having legal rights, duties and obligations such as suing and being sued, and entering into contracts.

Only a Natural Person can have human rights to the fullest extent but Legal Persons can have a right to, for instance, freedom of expression or natural justice. Any right that it makes sense for a Legal Person to have will also be accorded to the river. If the river is by any legal means considered to be supplying goods and services, it will be liable to pay the Goods and Services Tax the same way that a company would. If corporate manslaughter laws were introduced in New Zealand it would be possible that the river could be held liable for the death of anyone who drowned although it stretches the bounds of our understanding of liability to understand how it would be enforced in the civil or criminal realm.

Significantly, the expansive definition of the river’s legal personhood at s 14(1) above is moderated by s 14(2):-

‘The rights, powers, and duties of Te Awa Tupua must be exercised or performed, and responsibility for its liabilities must be taken, by Te Pou Tupua on behalf of, and in the name of, Te Awa Tupua, in the manner provided for in this Part and in Ruruku Whakatupua—Te Mana o Te Awa Tupua.’ – s 14(2)

The role of Te Pou Tupua – two natural persons – who are the agents of the river as a legal person are discussed further below. It appears to be a clear statutory construction that their capacity is delimited by the legislative purpose of protecting the health and wellbeing of the river. This would seem to circumscribe the possibilities of this legal status extending into things for which individuals would be considered liable such as offences against criminal law.

This all seems very abstract at first blush so it is helpful to look at the origins of this idea and the problems it was designed to solve. I wrote about this in my Master of Laws thesis at the University of Auckland in 2010 and have summarised my research below. Continue reading →

The

The  This marks the conclusion of the longest-running piece of litigation in New Zealand legal history and is particularly remarkable in extending legal personality to the Whanganui River. Although, this is not a first in New Zealand as Te Urewera (a former national park) was

This marks the conclusion of the longest-running piece of litigation in New Zealand legal history and is particularly remarkable in extending legal personality to the Whanganui River. Although, this is not a first in New Zealand as Te Urewera (a former national park) was

As

As